Each of the Gospels in the New Testament tell the story of Jesus differently. They are not simple biographies with a timeline or a collection of news stories reporting facts. They weave together a narrative designed to communicate unique truths and insights about Jesus.

For example, the first part of Mark’s Gospel shows a wildly popular Jesus. In Capernaum, after Jesus’ first miracle, the ‘whole city gathers around’ him to be healed or watch him heal. The disciples talk about how ‘everyone is searching for you.’ Four men have to cut a hole in the roof and lower down their friend because of the crowd in the house where Jesus is staying. He feeds a crowd of over 5000 people, and then another crowd of 4000 people.

And yet, there is a turning point in Mark’s story. The tone and the direction of the story becomes very different.

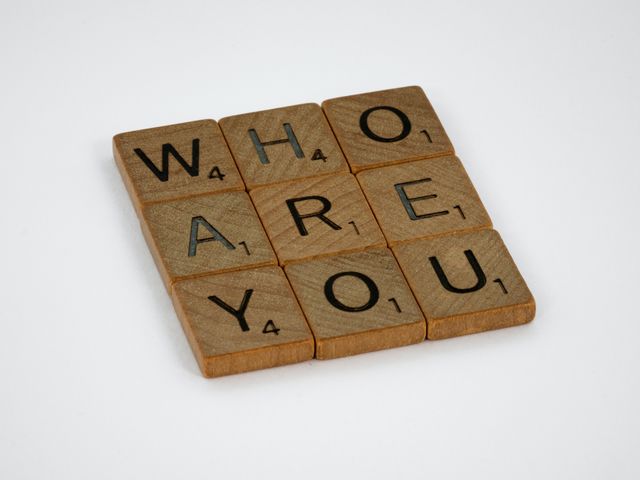

The crowds begin to dwindle, except for those who are opposed to him. There is talk of denying self, taking up crosses, losing your life to find it. There are even predictions of impending death. Mark’s story goes a completely different direction in response to a question that Jesus asks of his disciples: Who do you say that I am?

Actually, this question is a follow-up to a previous question: Who do people say that I am? Because of Jesus’ popularity, there many, many answers to that question. The disciples had heard many of them. Perhaps they discussed these various responses among themselves as they were sitting around the campfire at night, because even as his followers, they, too, were trying to figure exactly who Jesus was and what he was about.

What was happening then has been happening for over 2000 years. Think of all the words written and spoken about Jesus. Think of all the books written and sermons spoken. Think of all the discussions in classes and seminars. Think of all the people who stand every Sunday and recite creeds from a place of deep faith. All of these are efforts to answer that question.

It is vital that we twenty-first century Christians get a sense of how those outside the faith think of and perceive Christ. Vital, because who they perceive Christ to be is related to how they perceive Christians to be. If, as some studies suggest, the view outside looking in, is that Christians are judgmental and unloving, then we need to ask: What can we do about the aspersion this casts on the identity of Jesus whom we say that we follow? If Christ’s reputation suffers because of how many who call themselves Christians live, then what are we going to do about it?

Perhaps the best way to answer these questions is to consider the question from Mark: Who do you say that I am?

It is a turning point in Mark’s story. It was a turning point that day in the life of his disciples. It can be a turning point in our own stories.

When Jesus asks the first question about what others are saying about him, I imagine the answers came fast and furious. But with the second question, there is a deep and thoughtful silence. This is not a test question with the right answer. It is an invitation to consider what place, really, does Jesus have in my life. If we have chosen Christ, then why? Who is he to us? Who are we becoming as we live into his identity that resides within us? Who do we say you are, Jesus, and what difference does that our lives?

I mentioned earlier that there is a change in the tone and direction of Mark’s story after this scene. Could it be that this change comes because the rest of the Gospel includes various attempts by his followers to wrestle with this question? After all, Peter has an answer: You are the Christ. And yet, it is very clear in the conversation that ensues between Jesus and Peter that Peter doesn’t understand fully the words he has spoken. It’s not that Peter’s answer is wrong; it is just incomplete. And there be many more opportunities for him to hear and respond to the question.

What is true for Peter is true for each of us who proclaim, in some way, to be followers of Jesus. Life will give us many opportunities to wrestle with this question.

But sometimes it is helpful to give our attention to this question intentionally.

So, right now, imagine Jesus standing before you, however you picture him to be. See the look on his face and even hear the tone of his voice as he asks: But what about you, Gary (insert your name here)? Who do you say that I am?

What words come to mind? Perhaps you can even say them out loud. What happens inside of you when you answer? What is the look on Jesus’ face? Do the words reflect what you really feel in your soul, or are they really just variations on words that you have heard from others all your life?

Do the words sound like words that most people around me would say or agree with? Because if that is true, then maybe I need to stay with the question a little longer.

Who do you say that I am? Don’t answer the question as a liberal or a conservative. Don’t answer the question as a Republican or a Democrat. Don’t even answer the question as a Christian. Answer the question as you, as the person standing before this one who yearns to hear your response. Are the words coming out of your mouth words that you never imagined saying, but seem right and true?

By continuing to respond to this question throughout our journey, we continue a conversation with Jesus about our lives and his place in them. How I answer ‘Who do I say you are?” is also answering “Who do I say I am?” How connected is my life to the life of this one who I seek to follow? The answer to that question is not a label or description or a creed. It is an active power and presence in my life.